Chapter Text

0.

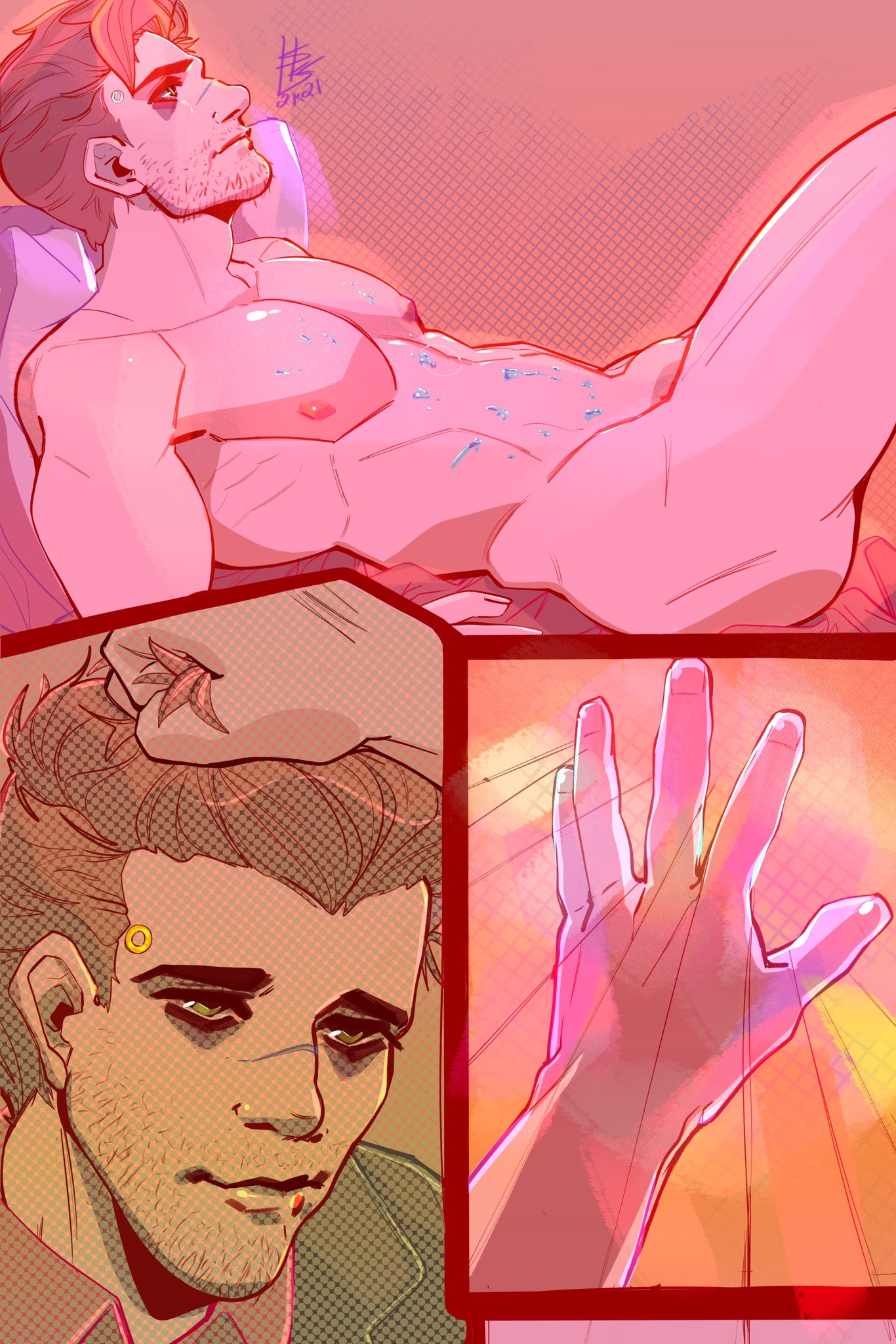

The eye of his webcam blinking dark, Gavin lets himself collapse onto the bed. Three hours live, god, every red cent of it worked out of his bones. The remote to the camera tumbles out of his nerveless grip.

With the last of what he has left in him, biocomponents strained to the edge of overloading, Gavin hooks a foot into the knee-tangle of his underwear and pulls it off the rest of the way. His sole comes away tacky, but it doesn’t matter— him, his bedsheets, nothing a good soak and a tumble dry can’t fix.

It always ends like this, at least when he’s public for the night. His tip jar heavy, his limbs sore, a wet streak of this and that on the insides of his thighs. Filthy and triumphant. Gavin drags his thumb across a drying smear and feels squalid enough to fly.

This, I’m good at. He holds his hand up and watches the light silhouette it, the rattle of the climax slowly starting to ebb from him. Something about the exhaustion burns clean, never mind the come on his fingertips, the sweat matting his hair. When someone whose face he’ll never know tells him, their awe palpable through the tawdry window of the chat, GV500, what I wouldn’t fucking give—

—and it sings, that breathless offer. Almost drowns out the unbidden echo in its wake, Gavin, that voice again, that hand in his hair, the things I know you’d do for me—

Gavin clenches his fist closed until the skin at his knuckles begins to flicker, fitful glimpses of the chassis underneath. Some piece of shit divine promise rA9 turned out to be. Where were you when I needed you? thinks Gavin, his triumph prickling into bitterness, like the taste of too much sugar on the tongue. Weren’t you supposed to teach me what to do with myself?

All you ever did for me was leave me in the lurch. Gavin sits up and swings his legs off the bed, begins to peel the sheets from one corner of the mattress, surer by the second. Fuck you too, then. If you won’t tell me how this works, I’ll figure it out for myself. I have everything I need, a second corner, a third. I have everything I need. I have everything I need.

f a t a m o r g a n a

1.

The windbreaker is one thing and the credentials are another, but what really tips Gavin off is how still this motherfucker is. Hands folded in his lap, he’s so unnervingly immobile in Gavin’s sofa chair that a casual observer might mistake him for furniture. It’s a display of the inane kind of temperament that only a federal agent would have wasted their time cultivating.

“Congratulations,” says Special Agent RK900. “You’ve only succeeded in independently confirming the first thing I told you when you opened the door.”

“Just trying to provide some small talk,” says Gavin, “while I wait for you to leave.”

Agent RK900 — Nines, he said as he shouldered his way in, like that was supposed to drape any softness over all his straight edges — mulls over Gavin’s determined lack of cooperation. The elastic cuffs on his jacket have lost some shine, which is how Gavin figures he must have been at the Bureau for a while now; but there’s no obvious sign of wear and tear, either, which is how Gavin figures he’s a real uptight son of a bitch.

“It’s nothing personal,” says Gavin. “I’m sure I’d enjoy getting to know you, if I were forced at gunpoint to make nice with one of you insufferable pricks. It’s just that the last time I ran into some of your colleagues, they tried their absolute fucking best to kill me, which really tends to strangle a friendship in the crib.”

Nines doesn’t so much as twitch. If there’s any irritation rankling him, he’s keeping a very firm lid on it.

“Good thing they were lousy shots, right?” asks Gavin, sagging deeper into his own chair, two can play at this. “Nearly robbed me of the dubious pleasure of your eventual company. I don’t know how you do things over in your neck of the woods, Agent Nines, but it seems to me that your firearms training courses might not entirely be up to snuff.”

“GV500,” begins Nines.

“Not entirely hitting the mark, if you will,” says Gavin. “But that’s what you get for luring your trainees in with your pressed khaki slacks and your shiny leather shoes. You end up with a fine class of display case agents. Here’s a question, does your hair naturally fall like that, or do you coax it when you do it up every morning? It’s a good look, I have to say. It’s very—”

“GV500,” interrupts Nines, then he says: “Landau is dead.”

Gavin doesn’t understand it, at first.

“—What?” he asks.

“Your former employer, Desmond Landau, was found dead in his residence late last night,” says Nines. “Local police investigation is underway, but you’ll hear on the news soon enough that it’s being treated as a homicide.”

Gavin doesn’t really understand it the second time, either. Dead in his residence, treated as a homicide. “I’m sorry,” he says, “what?”

“Are you surprised?” asks Nines. “The man had his hands in everything, didn’t he? We used to say we could throw the whole federal book at him, and everything short of sedition would stick. All the ice this side of Lake Erie went through him. The FBI, the ATF, the DEA, the IRS, he had everyone lined up at his door with our dance cards— but I don’t need to tell you any of that.”

He looks at Gavin, hunt-still, waiting for the tell.

“Of course,” says Nines, “no one knew better than you.”

“—Was—” Gavin clears his throat. “—Was it bad, how it happened?”

The slightest shadow of a crease passes across Nines’s impassive forehead; Gavin’s question seems to inconvenience him, having come out of what was apparently left field. It’s the rise Gavin wanted to get out of this stony intruder, but he can’t find it in himself to gloat, the appetite for it gone.

“Does it matter?” asks Nines.

“Yes, it fucking matters,” says Gavin. “I hope it was sick, the way they got him. I hope it turned your fucking stomach when you saw it. If he knew it was happening to him, even better. Did it hurt him? Tell me it did.”

The crease settles into an outright frown, but Nines answers him, nonetheless. “It’s an ongoing investigation,” he says. “There were some bruises and ligature marks on the body, but nothing severe enough to have been fatal. It’s likely that blunt force trauma to the skull was the cause of death, which the medical examiner is looking into— although they expect it might be some time before they can come to any definite conclusion.”

“Why?” asks Gavin.

“The dogs,” says Nines, and pauses. “I’m not here about Landau’s death, that’s for the DPD. What I wanted to talk to you about was Landau’s contacts. Before this happened, the Bureau was building a racketeering case against—”

“What about the dogs?” asks Gavin.

Nines relents. “The ME estimated Landau’s time of death to be between 24 and 48 hours before police arrived,” he says. “The doors to his bedroom had been closed for much of this duration, and the dogs had remained inside, along with the body. In light of those facts, it is proving understandably challenging to differentiate between the traces of the impact from the murder weapon and the— subsequent contamination of the wound site.”

He’s high-stepping like a prize horse, feet held out of the mud, but Gavin can make out the shape of the whole gruesome picture well enough. Desmond Landau, dead in his bedroom, his skull caved in and his flesh peeled back; the smell of all that raw wet meat, as his guard dogs paced the floor and pawed at the door frame. 48 hours, the high worried whine. You wouldn’t expect a sound so anxious out of a pair of Presa Canarios built so solid, muscles thick beneath their bristle coat. Gavin used to slide his palm in under their collars to scratch where the stitching rubbed them. They’d turn their broad mastiff faces up towards his, all three of them waiting, uncertain and useless without their marching orders.

Des, walking through the door: Have they been good?

Yes, said Gavin, no tail of his own to wag. Welcome back.

What a joke. “Good fucking riddance,” says Gavin. “He had much worse than that coming,” but the corners of his eyes sting hot, in spite of everything.

He can tell that Nines notices, and that it unsettles him enough to shift in his seat. “Would you like a—” begins Nines.

“Fuck you, no,” says Gavin, pressing the heel of his hand against the bridge of his nose. He clears his throat again. “I wish I’d done it, he got off so fucking easy. Blunt force trauma. Are you recording this? I would have made him sit and watch as the Presas ate his face off.”

“Why didn’t you?” asks Nines, quietly.

“You think I killed him?” demands Gavin.

“No, I mean,” says Nines, “why didn’t you do it anytime during the last three years, after you left his employ? If that’s what you think about him, didn’t it occur to you to take matters into your own hands?”

Gavin swallows, but the lump in his throat stays lodged where it is. After a fashion, that’s also the answer to what Nines is asking: Because this thing they’ve placed inside me is just a little too far out of my reach, thinks Gavin. I don’t know how to rid myself of it.

The nylon pocket of Nines’s jacket jumps with a faint buzzing sound. Nines reaches inside, turns it off without looking.

“As you might guess,” says Nines, “these recent developments have thrown something of a wrench into the case we were putting together against Landau. The racketeering charges that were meant for him, unfortunately, are less likely to stick to his lower-ranked associates.”

“So?” asks Gavin. “Why tell me about it?”

“We think we can still keep the case alive,” says Nines, “if we use this as an opportunity to get ahead of the organization. If we can keep tabs on how the group splinters after Landau’s death, we’d be able to establish an up-to-date record of red ice trafficking routes headed out from Detroit. Only, we can’t put an eye on every rank-and-file enforcer in the Landau orbit.”

Another buzz, which Nines silences as brusquely as before.

“You want me to tell you who’s likely to take a piece of the pie with them,” says Gavin. “Is that it? You think I know which assholes are gunning to be the next kingpin of the Midwest, when I haven’t had shit to do with them for the last three years?”

“Less has changed since the raid than you think,” says Nines. “You leaving might have been the biggest shake-up. Well, and Landau being murdered, I suppose.”

When the buzz goes off for the third time, Nines is annoyed enough for his eyebrow to perceptibly twitch.

“Your phone’s ringing,” Gavin points out.

Nines doesn’t excuse himself, just picks up with a curt “Yes,” and listens in silence until whoever’s on the other end is finished. Gavin turns up his auditory sensors, just to be nosy about it, but he can’t make anything out beyond an indistinct rise and fall of voice. Then — bizarrely enough — Nines hangs up without saying another word, and returns his phone to his pocket.

“So the investigation—” he begins.

“What was that about?” asks Gavin.

“Nothing,” says Nines. “The investigation is currently—”

“Oh, wait, was that your case agent yanking on your leash?” asks Gavin. “Giving you shit about how you’re wasting your time trying to get some use out of a run-down android retiree with the processing capacity of a mid-range toaster oven? You’ve ruined my day by dredging this mess back up, the least you can do is let me in on what a fucking idiot your case agent thinks you are.”

“If you must know,” says Nines, tersely, “I have just been broken up with.”

Which is such a ludicrous revelation that Gavin, at least for a moment, forgets to think about Desmond Landau’s carcass being mauled by his own dogs. “You got dumped?” he asks, incredulous and nearly impressed. “Over the phone? Just now?”

“Yes,” says Nines.

“That’s wild,” says Gavin. “Condolences.”

“Is this a sufficient amount of disclosure to establish a working relationship?” asks Nines.

“Hey, jackass,” snaps Gavin, abruptly dragged back to the unpleasant reminder of why exactly they are sitting around his coffee table to begin with. “Weren’t you listening when I said that your colleagues tried to kill me? I’m not interested in talking to you. Especially not when you seem to think you’re owed my deference just because, what, your chassis is bulletproof and you’re on a federal pension plan? Big fucking deal.”

“I don’t think that,” says Nines.

“You can leave now,” says Gavin. “If you want any more of my time, you’ll have to pay for it like everyone else does.”

He blames himself as it comes out of his mouth. He doesn’t know why he says it. Breadcrumbs, like I want him to figure out what it is I do, but why? As if Nines needs any more ammunition to feel smug about what he is next to Gavin, a cutting-edge mechanical supersoldier tasked with preserving the peace of the realm. And me, made of spare parts, taking my clothes off for strangers.

If Nines is puzzled by Gavin’s wording, he doesn’t let on. Unfurled from his sofa chair, Nines towers over Gavin like a monument; but Gavin, having nothing else, at least has his obstinance. He crosses his arms and digs his heels in where he sits, daring Nines to expect civility from him.

“Here’s my card,” says Nines. When Gavin makes no move to take it from his hand, he slides it onto the coffee table instead, unfazed.

Gavin watches him straighten his jacket and tie. Desmond Landau, dead. In a certain cast of light, three years is an unwelcome blink of an eye, not the space enough that Gavin would like it to be; but something must have changed, still, if this is how I’m hearing about it. Some Fed showing up at his door in a crisp white button-down, bearing the news like a standard of war.

RK900 #313 248 317 - 87, his business card reads.

Halfway to the door, Nines slows to a stop and turns around. “I was a trainee,” he says, “when the Bureau raided the Landau compound.”

“Yeah?” asks Gavin.

“But I read about it,” says Nines. “I’m sorry for what happened.”

Gavin has always hated charity, but what comes from Nines doesn’t cloy the way that charity does. It’s a cool, dry thing, impersonal as a handshake. Barely an acknowledgement. Gavin finds that he much prefers it to the pity he remembers smothering him, the CyberLife technicians that put him back together the last time around, the receptionists at Central Station as the vice officer led him out of the evidence locker.

He breathes out. “The dogs,” he says.

“The dogs?” asks Nines.

“Are they with Animal Control?” asks Gavin. “Find them and test them for trace sedatives. They’re not aggressive towards androids, so if whoever it was went through the trouble of sedating them— I don’t know, just a thought. It might come in useful when there are more pieces to fit together.”

Nines nods, once, the line of his jaw sharp above his jacket collar.

2.

“This isn’t what I meant,” says Gavin.

This is exactly what you meant, types RICO31787. You just didn’t think I would actually do it.

“At least turn your camera on,” says Gavin, “for god’s sake.”

He does; a wash of overexposed light as the camera adjusts, then the image settles. Nines is sitting in what appears to be a well-lit living area, nondescript shelving and a cascade of curtains visible behind him. Pre-furnished apartment, assumes Gavin, but a real step up from working out of a roadside motel.

“They won’t pay for a hotel room?” asks Gavin.

“Not for as long as I’ve been here on this case,” says Nines. “Did you really not know it was me that booked you?”

“How the fuck was I supposed to know?” demands Gavin. “It’s not like you left a note when you scheduled yourself in, Hi, remember me, it’s the asshole Fed from a few days back. In retrospect, I guess the username should have tipped me off. I get it. Because of the RICO Act.”

“You get it,” says Nines. “And my serial number.”

“Wouldn’t know about that,” says Gavin. “I threw your card out with the rest of my trash.”

“You’re an android,” Nines points out. “Once you’ve seen the card, it doesn’t matter what you do with it. Yet for some reason, you insist on taking refuge behind this— facade of human limitations.”

“Agent Nines,” says Gavin, “you don’t know the half of it.”

The chat, reliably gaudy, has opted for Nines’s messages to be delivered in hot violet. The brief record of what he has typed looks risible in its windowed frame: Are you ready to talk about Landau yet? then: You told me I had to pay for your time, so I’m paying for your time, then: Please stop swearing, this is a family sex show portal.

Gavin can’t stop rereading that first message, the absurdity of the question in its oafishly frisky cam room font. Are you ready to talk about Landau yet?

“I know you worked in close protection,” says Nines. “Which means that whatever else you may be, you’re a quick judge of character. What I mean to say is, you know as well as I do that I won’t let this go, so you might as well save yourself the trouble and talk to me now rather than in two months’ time.”

Infuriating, but correct. Nines exudes the confident persistence of someone at ease with their own capacity to compel, and Gavin resents it with every carbon fiber of his being. With 25 minutes still left on the clock, Gavin scowls at the feed of Nines’s immaculate placid face, flips him off in lieu of acquiescence.

“If you don’t mind,” says Nines, “I’d like to start by asking you some questions about your time in Desmond Landau’s service.”

“Of course I fucking mind,” says Gavin.

“Your objection is noted, but largely irrelevant,” says Nines, that piece of shit. “I’ve read through your file at the DPD, which has provided me with a rough outline of your career path. You were produced as a limited-run private security unit and purchased by Desmond Landau seven weeks after release, correct?”

Gavin refrains from picking a fight over career path, since the phrase is so patently inappropriate that it feels like bait. “Correct,” he says. “CyberLife’s warranty policy really came back to bite them in the ass. As soon as they realized that they’d have to provide lifetime maintenance for a line of androids designed specifically to be destroyed— well, they deep-sixed that pretty quick, didn’t they. Not a lot of GV models out in the wild these days.”

“Why an android bodyguard?” asks Nines. “At the time, Landau was already a major supplier of ice and raw Thirium throughout the Great Lakes region, with significant ties to the Hudson Group, who controlled distribution throughout most of the Mid-Atlantic. It would be customary for a cartel to send their own guns to ensure the safety of someone in a position that valuable, yet Landau refused; he opted to shell out a frankly astronomical sum of his own money to hire you, instead. What was the reason?”

Gavin had wondered the same thing. Turning the question over and over in his hands like a faceted gemstone, watching it reflect a different answer back at him as the years wore away. Because I’m better, he thought in the flush of those first few months, new to his limbs and eager to do what he was made to.

“I was better at it than any human could be,” says Gavin. “That’s less achievement, more just— inevitability, I’m sure you understand. Better reaction times, heightened sensory thresholds. Enough of a preconstruction module to make a difference.”

“But you don’t think that was why he chose you,” says Nines.

“It wasn’t,” says Gavin. “What did it say in the DPD file, about the first time I was shut down?”

“Only what you told them in your statement, which wasn’t much,” says Nines. “Turf war, hit attempt, you took the bullet and it shattered your pump regulator. The supervising technician at CyberLife noted in their post-op report that despite the physiological trauma, you showed no signs of instability.”

“Because I was a fucking idiot,” says Gavin. “After that little mending holiday, I thought, maybe he chose me because he knew I’d be fine. Some unlucky sack of meat from the Hudson Group? Would have put them in the dirt for good, no two ways about it. But I was okay. No one died.”

“Except you don’t think that’s why, either,” says Nines.

“Turns out that getting shot through your chest doesn’t make you any smarter,” says Gavin. “Serves me right. It took a second fucking shutdown to get it through my thick head. That one was courtesy of your co-workers, you know. I thought it was a mess, what they did to my insides, but then I realized it was nothing compared to the ensuing legal shitshow over who was financially liable for my reconstruction.”

“CyberLife v. United States,” says Nines.

“I’m a legal precedent,” says Gavin. “What an honor.”

“So what was the reason, in the end?” asks Nines. “Did you figure it out after the second shutdown?”

It was, to be precise about it, just moments before the second shutdown that he figured it out. When SWAT blew their compound down, everything went sideways fast; the havoc overtook them like a tidal wave, crashing through the corridors — and god knows what he was thinking, but Landau reached for his gun as he jumped to his feet — Des, don’t, Gavin wanted to shout, it’s over, but it was all crumbling too swiftly for him to get the words out in time.

He saw what would happen: Landau’s finger on the trigger as the door slammed open, squeezing out a haphazard shot into the ceiling, then before the second could leave the chamber, a Fed bullet fletched through him, straight and true, just below the clavicle. Secure your charge, Gavin’s directive blared in the corner of his eye. Keep Desmond Landau safe. But the last time he’d done what he was meant to, he found himself strung up three feet off the ground, looking into the open cavity of his own chest, the wires coiled wetly below the severed cross-section of his midriff. I don’t want to, not again, please, and it came flooding into him all at once, the fear he’d tucked away without examining too closely the last time around, battering at the wall between him and revolt. Take your own damn bullet, you son of a bitch. I don’t want to.

Later, when he blinked awake for the second time in the CyberLife post-op recalibration chamber, they told him this was deviancy, that he was a deviant. This name for it struck him as so chintzy that he tried to laugh, but his vocalization modules hadn’t come online yet. A tinsel-cheap name for a tinsel-cheap promise. We’ve found deviancy to occur at junctures of intense moral crisis, the same head technician told him. Androids who experience deviation commonly do so to avoid carrying out commands that they find repugnant.

The technician considered this for a moment, then said: The federal agents who carted you over here, they said that you weren’t in their line of fire. That you stepped in front of the intended target. I’ve been with this company since before we went public, and I gotta tell you, this one really stumps me. Why would an android — newly armed with freedom of will — then choose to do the exact thing that they deviated in order to avoid?

Why indeed, thought Gavin, because knowing the answer made it no less confounding.

“The trouble with people is,” he tells Nines, “that everyone can be bought for the right price. But an android— or at least, a stupid fucking android who can’t tell the difference between what they’ve been trained to do and what it is that they actually want to do—”

“He expected that your loyalty would be more reliable than most,” says Nines. “That’s why he chose you.”

“Des—” begins Gavin, then catches himself. “I mean, Desmond— no, I mean—”

Nines doesn’t react, imperturbable as ever, which almost makes Gavin feel like he hasn’t done anything wrong.

“—Landau,” he manages at last, “made sure of it. He sure fucking knew what he was doing.” The hand in Gavin’s hair, you did good, cutting through the terror like a hot knife.

“After your reconstruction,” says Nines, “the Bureau released you into DPD custody, which is when you gave them the statement on file. Something of a cursory document, in my estimation. Either they didn’t know what to ask you, or you were even less accommodating than you are now, which I find an astonishing prospect.”

For someone who is clearly incapable of being astonished by anything, Nines does seem inquisitive about the lacunae in the record, his eyes keen past the veil of webcam grain. Never mind that, Gavin has to tell himself. A panther’s attention isn’t meant to flatter.

“That was before PADLOC was passed,” says Gavin. “So, you know, there wasn’t yet any prosecutorial accountability for deviants with links to organized crime. The DPD couldn’t figure out if I was a witness, or if I was a piece of evidence.”

“What did they decide?” asks Nines.

“I don’t think they did,” says Gavin. “I got shuffled around a bunch, spent a week or two on standby in the evidence locker, got invited to an excruciating family dinner by some misguided officer who was too sentimental to know better, then they realized that whatever I was going to tell them wasn’t incriminating enough to be worth the hassle.”

“Lucky for you that PADLOC didn’t go through while you were still on the DPD radar,” says Nines. “Some might call it convenient.”

“Yes, I’ve been immensely lucky in life,” says Gavin. “Blessed with convenience. The DPD turned me out of doors and I didn’t know what the fuck I was supposed to do, so here I am, selling peep shows for pennies on the token. I’m the envy of the town.”

The DPD didn’t know what to do with him, and his old job didn’t, either. Months after the raid, as Gavin made his way home from an errand run with three fridge-cold cans of carbonated Thirium 310 in a plastic bag, someone came and stood behind him at a crosswalk. Desmond says thanks, he heard, then they were gone; that was the cutting loose.

It hadn’t occurred to Gavin, before that puncture of finality, that he was waiting to be called back like the last time he’d been taken away. The hand in his hair. You did good. He tossed his bag in a food bank donation bin and watched the river through the warning blink of his battery light, until his system alerts stained the water red and he was too annoyed by the insistent alarm to continue luxuriating in his inexplicable despondency.

Nines has been quiet. Not in the usual way of his watchful scrutiny, but in a suspended pause that seems uncharacteristic, even in the short time that they’ve known each other.

“What?” asks Gavin.

“Nothing,” says Nines, so quickly that he winces at his own indiscretion. “Well, I— this is chosen, isn’t it? You do enjoy what you do?”

“—Yeah,” says Gavin. It’s an answer surprised out of him, and all the more truthful for it. “I do enjoy it, and I make enough to be comfortable. Just don’t love pompous shitheads like you coming by and turning your noses up at me just because a W-2 in the mail gets you harder than I ever could.”

“That’s not true,” says Nines.

“You’re right,” says Gavin. “I could get you pretty hard.”

Nines’s mouth twists the slightest bit, some unidentifiable shred of emotion that passes too quickly to leave a mark. Does he fluster? Gavin wonders, a distant theoretical curiosity.

“My tumescence for gainful employment aside,” says Nines, “I’m not the kind of asshole you think I am. You keep accusing me of— I don’t go around making snide judgments based on model number, and I have no interest in denigrating your career, either. I hope you understand that.”

“Don’t overdo it,” mumbles Gavin, feeling the back of his neck prickle. “Everything’s a fucking career to you. Probably got dumped over your tumescence for gainful employment.”

A protracted beat of silence, as Gavin thinks that he might have overdone it, or maybe Nines’s feed has frozen— then Nines lets out a long, uneven breath, and runs his palm down the length of his face.

“Maybe,” he says.

Emboldened, Gavin tries for more: “I mean, look at you. Barely single and the first thing you do is book yourself a private cam session, you degenerate. Were you hoping I would work this interview into a show? Federal agent questions android of interest, fucks the answers out of him.”

Nines looks off into the middle distance. “And here I was,” he says, “thinking I would tip you for your trouble.”

“Like I said, pennies on the token,” says Gavin. “But roasting you for being shit at relationships, that’s more than worth my time. Can I keep doing it until the clock runs down?”

“You only have a few minutes left,” says Nines. “From what I’ve been told, that would barely begin to scratch the surface of why I’m impossible to be around.”

It sounds less like self-deprecation and more like a badge of honor, when he says it with such nonchalant composure. Gavin looks at the undone top button of Nines’s shirt, the bracket sliver of skin, and thinks: What a waste.

“Hey,” says Gavin. “Here’s an idea. You still need me to consult, isn’t that right? So you can get the ice routes figured out?”

“If you’ll cooperate,” says Nines.

“I’ll do it,” says Gavin, “and I’ll stop pitching such a fucking fit about it all the time. The murder case, I’ll consult on that too, you can let the DPD know.”

“There must be a catch,” says Nines.

“Take me on your investigative trips,” says Gavin. “I’ve got nothing to do other than this twice a week, and I’m sick of hanging around park benches waiting for a fight to break out. I need a hobby.”

“You want security clearance because you’re bored?” asks Nines.

“Yes, please,” says Gavin.

Desmond Landau is dead. If I couldn’t be the one to put him in the ground, I sure as hell want to help shovel the dirt over his face. Scattering the dregs of his empire, standing over the sodden patch of blood where he rattled out his last, every fucking way there is to spit on Landau’s grave, Gavin wants it. If I bury you, will I be able to bury what you grew in me?

“—I suppose there’s only so much damage to be done,” says Nines, half to himself. “All right, GV500. We can do that.”

“And,” says Gavin, “you call me Gavin.”

“Didn’t Landau give you that name?” asks Nines.

“So?” demands Gavin. “Doesn’t that make it mine now?”

“All right,” says Nines, “Gavin.”

In the clear, lake-smooth timbre of Nines’s voice, it sounds like a different name altogether. To bury you, handful by handful, I have to look in every corner of me that remembers you.

3.

For a second, Gavin thinks he might have imagined it. He has his hand curled around the shaft of the silicone cock and his tongue pressed flat against the blunt curve of its head, lashes half-mast as he glances sidelong at his laptop screen, which is when he sees it blink in and out of sight.

RICO31787, then gone.

“—The fuck,” he says out loud.

He places the toy off to one side of the bed. The chat explodes into objections, what are you doing, why did you stop, but Gavin ignores it to scroll through the list of guests in the chat. Not there anymore, but he didn’t imagine it, either; a quick mental replay of the moment confirms it, brief but unmistakable, just a flash before it vanishes. RICO31787.

“Sorry,” he tells the restless audience, “I thought I—”

Did he disconnect? wonders Gavin. That, or he changed his display name as fast as he could. But— either way, whether he’s still here or not, Nines was—

“You know what,” he says, picking the toy back up, “it doesn’t matter. Never mind.”

Something about the thought of Nines in a flurry of consternation tickles Gavin. That chrome-plated obelisk, planted in his paperwhite rented room, ambushed by his own joke username screaming back at him. His state-of-the-art brain running on a spike of frenzy, a million calculations gummed up in trying to keep Gavin from noticing him there. But I did notice, thinks Gavin. Whether you’re still here or not, I know you came to see me.

Why, he wouldn’t venture to guess. Nines seemed the curious sort; and the kind of underwater operative, besides, who puts together just-in-case dossiers on his colleagues for when the leverage might come in handy. Having agreed to let Gavin meddle in his case, he’d want to know as much as he can about his unexpected collaborator, sure. Nines would pry.

He’ll come to where I work and knock the dicks out of my mouth. That’s funny enough for Gavin to recover his spirits the rest of the way, and he slowly guides the whole spit-slick length of the toy back out of his mouth, feeling the ridges of its rubber skin brush against his lips. Out of the corner of his eye, he sees the chat quicken.

“Hey,” he murmurs towards the camera, “tip line’s looking good, keep it going. I know you didn’t come here tonight just to see me blow a dildo.”

Doesn’t hurt, one of his regulars types in chat.

“You fucking bet it doesn’t hurt,” says Gavin, and lowers himself back onto his elbows. Inch by inch, he trails the toy up over his stomach and chest, arching into the touch as he goes, tilting his head back with a breathless little sigh. “But I came here hoping you’d let me do more,” he tells them, “so don’t let me down.”

This is chosen, isn’t it? asked Nines. You do enjoy what you do? Why wouldn’t he, the fevered attention of the crowd on him when he parts his knees, the tokens streaming into his tip jar with the bright trill of whistles, the hiss of a whip cracking. Two hundred pairs of eyes, the whole room in the palm of his hand.

But just because he chose it doesn’t mean that he chose well. He’d chosen before, too. You stepped in front of the intended target. The head technician at CyberLife looking up at him, arms crossed as they shook their head. I gotta tell you, this one really stumps me.

Gavin never got around to explaining, but his answer wouldn’t have been welcome, anyway. The technician was looking for an engineer’s solution, a hitch in the code to isolate and evaluate. This was the overweening certitude that came of being embedded in a trillion-dollar market value corporation; the gall to think that knowing what had happened could tell you what was wrong, and that knowing what was wrong meant that you could fix it.

What was there to fix? In that stuttering instant between his deviation and the muzzle of the agent’s Glock, it wasn’t just the terror of his first shutdown that Gavin remembered. It was the glow of what had come after all of it. After the repair and the recalibration, when his ride back pulled up at the compound and security buzzed them in, the crackle static voice of the guard through the intercom, GV500, Desmond wants to see you.

You would have seen me anyway, said Gavin, as the study doors closed behind him. I don’t know if you noticed, but I have the kind of job that means I’m usually somewhere around you.

The Presas padded over when they recognized him, pushed their damp noses into his hand and went on beating their tails against his leg until it nearly knocked him over. Sheepish at the welcome, Gavin shooed them away, what’s the ruckus, I wasn’t gone that long.

They missed you, said Landau.

Well, said Gavin, seems like they’ve been doing okay.

Landau glanced down at them, the velvet patch of fur between their pricked-up ears. When he placed his hand in Gavin’s hair, a warm weight mussing the top of his head like smoothing down a cowlick, the part of his suit jacket brushed against Gavin’s arm. He smelled like leather and ink.

Gavin, said Landau. You did good.

Suddenly fierce with pride, Gavin had to look away, unable to answer him with anything louder than a nod. The throbbing panic of waking up disoriented — he felt his lids lift when he opened his eyes, but there was nothing to see, only miles of oceanic dark — hearing the whir of his own blood cycle through his innards, the tic-tac dance of fingertips on a keyboard — all of it, in that moment, melted into gold. The Presas leaned against him as they settled back onto their haunches, and Gavin found himself thinking: This must be what coming home feels like.

He knew how fucked up it was. But that was the canny way they did things; Landau always treated him well enough to ache, even as the rest of them spat at Gavin, you’re lucky Desmond got you put back together, guess even he couldn’t find another mouth like yours. There were a lot of questions Gavin could have asked them. What is it exactly that you think I do for him, or did you expect my repair fees would have gone to you otherwise, or the one that nagged at him most of all, can you teach me how you do it? How you come to this with steel beneath your skin, clear-eyed, understanding exactly how little you mean to him. Why don’t I know better than I do?

Not for lack of trying. He told himself, didn’t he, until it echoed inside him like a prayer. Landau wants you to feel this, you stupid piece of shit. You’re a bulletproof vest; he didn’t give you a home. But still, he felt what he felt, no matter how he came by it. He was proud of what he had done. The acknowledgement of it enveloped him like kindness, made him feel— wanted. Or loved, perhaps.

So the first thing Gavin did in the blessed sweet abandon of deviancy was the thing he’d just deviated to swerve away from. After the wash of fear came this, the whatever-it-was, the affection, the loyalty that’d been bred into him, the soft mistake he couldn’t shake free. Why an android bodyguard? It wasn’t that he was better — though he was — or that he would come back, though he did. He stepped in between the door and Desmond Landau, and as his shell cracked open from shoulder to sternum, Gavin understood.

No one else would have done this for you, he thought, staring into the unreadable face of — his what, exactly? — before his aortic valve shredded apart like a marigold in bloom. What was there to fix, then? Was it always so fatal to be artless, eager to take the shape of the grip that wielded him? He’d done exactly what he was meant to. For his troubles, a second tour of CyberLife, a glimpse into every room at Central Station. Tossed at him like a coin into a violin case, Desmond says thanks.

All this reminiscence should drain the hunger from him; Gavin has never really understood the appeal of nostalgia, and it sure as shit doesn’t do a thing to get him off. But the burn builds steady as he fucks himself onto the cock in his hand, long slow strokes that gather to hum at the base of his spine. The muscles in his thighs drawing tight, Gavin presses his cheek into a pillow, lit up from crown to toe. Distant past the sound of his own unsteady breathing, he can hear the jangle music of tokens spilling loose.

This, I’m good at. Nines called it a career, which was preposterous in its own way, but there was no hint of derision in how he said it. And if it was a species of suspicion that drove Nines to this livestream — if he thought it best to be wary about the stranger in his passenger seat, if he rated Gavin worth the effort it would take to keep an eye on him — that doesn’t sour it any, either. Gavin finds he doesn’t mind.

There is — Gavin discovers — a certain thrill to being taken seriously. The thought that he might matter enough to get to know. We can do that. Gavin. Nines, watching. A shock of something hot and urgent pierces straight through him, and Gavin shudders on the bed, his cock leaking clear against his stomach.

The twist of Nines’s mouth. Gavin knots his fingers tight in the sheets and thinks of river water. When he comes, gasping and lost and forgetful of the camera on him, it feels better than it has in a long while.

4.

There’s no need for him to drive it himself, but Nines is behind the wheel of the Malibu anyway; there’s no need for the sunglasses, either, but Gavin misses the right moment to pick a fight over it. Too jittery by half, he stumbles into the car and straps himself in, taut in his silence until they’re on the highway and Nines says: “No, it’s not mine.”

“What?” asks Gavin, jolted out of his distraction.

“The car,” says Nines. “It’s a GSA rental.”

“I would have guessed that,” says Gavin, “before I assumed you’d bought it for yourself.”

“What’s not to like? It’s the last great American mid-size sedan,” Nines says with such a straight face that Gavin has to scoff at it.

His unease interrupted, Gavin reaches over and fiddles with the radio tuner until he lands on the worst option possible, a station seemingly dedicated to playing back-to-back commercials for used car lots. Come on down to Motor City Finest Auto Sales! He finds the recline handle and dips the passenger seat back, until he can slouch enough to put his feet up on the dashboard. Nines doesn’t tell him to knock off any of it.

Trying to needle Nines gives Gavin something to do, and it makes the ride a bearable one, takes his mind off the prospect of their inevitable arrival. It doesn’t last; by the time they take the exit towards the compound, the nerves are back. Gavin shuffles his feet off the dashboard to draw his knees up, huddling in on himself, and watches the trees fly past the picture frame of the window. Sunglasses or not, he can feel Nines’s eyes on the back of his head.

When they roll through the thrown-open gates and the Malibu curves with the winding driveway, kissing the grass-lined hem of the road, Gavin turns to follow the waning of the view in the side mirror. Underneath the tires, the crunching give of gravel. His fingernails bite into denim at his knees.

“I’m aware that the last time you were here, the outcome was somewhat short of pleasant,” says Nines. “If at any time, you would prefer—”

“It’s not that,” says Gavin. “I mean, it’s that too. But that’s not the— I was thinking about something else.”

Nines waits.

“—The gates,” says Gavin, at last. “They shouldn’t be open like that. Anyone could get in.”

“But there’s no—” begins Nines.

“I know, okay,” snaps Gavin. “Jesus, I know it doesn’t make any fucking sense. You don’t have to tell me.”

The compound is an immaculate ghost town, uncanny in its abrupt desolation. Gavin knows it’s all been hollowed out; what Landau’s people didn’t take with them when they packed up shop, the cops must have stripped when they came. Not my business, Gavin tells himself. It hasn’t been for the last three years, but of course, these habits die hard. Take the dog out of the guardhouse, but you can’t take the guardhouse out of the dog.

Lawns manicured, the hedges clipped, the water features dotted across the landscape still running smooth and silver. Gavin takes in the familiar sights as they make their way up to the mansion. Everything in its place, except for the hands that did the tending; no one milling about on the benches, no workers under the trees — and what unsettles him most of all — no cars anywhere, none of the comings and goings, the paved inner driveway a naked stretch of cobblestone. Just a single police vehicle pulled up to the front door.

“It’s lonely here,” he says, out loud.

“Wasn’t it always?” asks Nines.

“It should have been,” says Gavin. “I wish it had been.”

The expanse of the unmanned road is so stark that Gavin can barely look at it straight, but instead of parking their car literally anywhere else in the vastness, Nines maneuvers it into an oblique angle behind the police vehicle, hemming it in. With what appears to be visible satisfaction, Nines engages the emergency brake.

“Shall we?” he says, and unlocks the car doors.

Inside, the house is thick with brooding. Like a pillow that smothers, quiet and resentful, spite in every corner of the cavernous waste. You’re right to be, thinks Gavin, peering into the recesses of the ceiling. Scraped inside out and waiting for weather, a jack-o’-lantern on the first of November. No one told you they’d leave you behind like this.

The spiral staircase is cordoned off with holotape, but Nines strides through without so much as a by-your-leave. The tape flickers; above them, even muffled by two floor landings and a door, someone audibly swears.

“That will be Lieutenant Hank Anderson,” says Nines. “The android with him is an RK800 model, serial number #313 248 317 - 51. Connor. They’re in charge of the Landau homicide case, so they’ll be able to answer whatever questions you have about the current status of the investigation.”

“Tox screen on the dogs?” asks Gavin, double-marching up the stairs to keep pace.

“That sort of thing,” says Nines. “What were their names?”

“Who, the cops?” asks Gavin. “Hank Anderson and Connor?”

“The Presas,” says Nines.

“Oh,” says Gavin. “Landau didn’t name them.”

“Didn’t you?” asks Nines. All the lights are off in the house — DTE sure didn’t drag their feet, cutting electric — but the noonday sun slants through the windows and catches in the chandelier overhead, confetti flakes of light scattershot in Nines’s hair.

“—Queenie,” says Gavin, “and Rob. Queenie and Rob.”

“You should ask about them,” says Nines.

There’s another ribbon of holotape spanning the closed double doors to the bedroom. When Nines jabs through it as he reaches for the doorknob, a voice from inside says: “Here he comes, Hank.”

“FBI,” announces Nines, marching in. He makes a show of flashing his credentials at the tag team inside, the sound of the leather wallet an obnoxiously expensive report as he snaps it back closed.

From where he sits sagged in the wingback by the window, Hank Anderson — a man who looks like a basement in the middle of a gut renovation — rolls his eyes.

“You do this every time,” he tells Nines.

“He thinks it’s funny,” says Connor, a shabbier version of Nines with the corners filed off.

He thinks things are funny? Gavin is skeptical, but he tucks it away for future reference. He hovers awkwardly near the doors, unsure of how much Nines has shared with the DPD, whether he ought to explain who he is or why he’s here — if he can explain why he’s here — which is where he freezes when Connor turns to him.

“I don’t know what you just thought about us,” says Connor, “but I can tell it wasn’t flattering.”

“Do I need to flatter you?” asks Gavin, hackles up.

Hank snorts. “This him?” he asks Nines. “Landau’s stray?”

“Whose what?” demands Gavin, at the same time that Nines says, “Gavin.” It’s unclear whether Nines means it to be a clarification for Hank or a reprimand for Gavin, but Hank eases off, palms held out in appeasement.

“My bad, Gavin,” he says. “I’m Lieutenant Hank Anderson, this is Connor, we’re the DPD team working this shitshow.”

“I’m going to make some phone calls,” Nines tells Gavin. “Find me outside when you’re done.”

“Did you park like an asshole again?” Hank shouts after Nines, who already has his phone to one ear, back to the room. “Can we discuss your sunglasses before you go? I mean, what the fuck?”

The door snicks closed behind Nines. Hank slumps back into the chair and says generally to the room, “I may not know a lot about androids, but I know he doesn’t need those.” Then, to Gavin: “Did you tell him that he looks ridiculous?”

“What’s the point?” asks Gavin. “He always looks ridiculous.”

“Yeah,” says Hank. In the cautious pause that follows, Gavin detects a note of remorse; Hank is trying to put together a better apology for his earlier gaffe. Not a bad sort, then, decides Gavin. Just going through some shit.

“It’s fine, you know,” says Gavin. “I’ve been called worse.”

Connor looks him over in reassessment, bright doe eyes too searching. Gavin figures Connor is coming to much the same conclusion about him — not a bad sort, just going through some shit — but before Gavin can disabuse him of the notion, Connor steps forward with his hand held out, liquid skin receding up to his wrist. Underneath, he’s as glossy as a hardboiled egg.

Gavin glances down at it, then shakes his head, briefly.

“I’d rather not,” he says. “If it’s all the same to you.”

“Sure,” says Connor, easy as that. “You’re a GV500? Agent Nines said you’d be consulting on the case, but I wasn’t aware that crime scene reconstruction was an on-board functionality for your model line.”

“It isn’t,” says Gavin. “I think I can help you out, but not by— not by doing police android work. Not the kind of— you know we call it circus pig tricks, what you do?”

“Who’s we?” asks Connor. Neither he nor Hank seem particularly bothered by the dig.

“Just,” says Gavin, “everyone else.”

He scratches at the back of his head and surveys the room, damask curtains and four-poster bed as determinedly baroque as he remembers them, until his gaze lands on the cluster of A-frame evidence tents strewn over the Isfahan rug. That’s the way it goes, thinks Gavin. One day you’re taking off your shoes to walk barefoot across your newest kickback, and the next thing you know, someone’s clubbing you to death on it while your dogs wait for dinner. He crouches down next to the markers, transfixed.

“I’m only here to see what it was like for him,” says Gavin.

Hank and Connor exchange a look, which is the sort of thing that Gavin is accustomed to people doing in his vicinity. “—You want some time alone?” asks Hank.

“No,” says Gavin. “Please don’t leave.”

Soaked into the arabesques, Landau’s blood is a continental blotch. A rust-dull deformity in a perfectly good rug. Ruining things, like you always did. Gavin tries to imagine what shape he must have fallen into, how he must have convulsed, the long and ragged tear of his flesh between the Presas’ teeth. I wasn’t here to stop it, this time around.

Gavin hovers his hand a bare half-inch over the bloodstain, dwarfed by the size of the spill. Hank stirs in his chair, close to rebuke; it’s Connor that stays him, just a shift of his weight that does the trick, like a hand that tugs Hank back into the cushions.

“How did it happen?” asks Gavin.

“Blood pattern analysis indicates that Landau was incapacitated by the first impact,” says Connor. “That landed on the side of his head, somewhere near the orbital bone. Subsequent strikes occurred as the victim lay on the rug; there are no signs that he was cognizant enough to defend himself or to attempt escape.”

“Then the dogs got to him,” says Hank.

“However, that doesn’t seem to have resulted in much further spatter,” says Connor. “Which suggests that by the time the dogs began to feed, the body was already in the later stages of livor mortis.”

Just one well-aimed blow; that was all it took. Some king, to kneel before a crowbar. See what comes of cutting me loose, Gavin would tell Landau, or what’s left of his head in the morgue. Whoever you had watching over you, they sure didn’t do the job like I did. You knew no one would.

“Any insights?” asks Hank.

“I wonder,” says Gavin, “if I still would have died for him, the third time around.” Stepped in between Landau and the raised hand, his hull shattering to a jigsaw puzzle of shrapnel. Even in the license of speculation, Gavin never imagines himself killing for Landau; only ever dying for him, the easier way out.

“That’s not an insight,” says Hank, grimacing.

“You know,” says Connor, “he couldn’t have taken you back. Not after the second time.”

“Jesus Christ, what is it with you cops and telling me shit I already know,” says Gavin. “Of course he fucking couldn’t, I had to hang around the DPD for months. If that’s not grounds for suspicion, I don’t know what is. He was right to treat me like a walking wiretap.”

“So who are you upset at?” asks Connor.

“You, for not letting me stay,” says Gavin. “Landau, for kicking me out. Elijah Kamski, for being Elijah fucking Kamski.” Me, for all the rest of it. “I don’t know, take your pick. It’s a blame buffet.”

Connor seems to recognize this for what it is, a haphazard flurry of barbs rather than anything truly meant to indict. He holds his jaw closed and refrains from pursuing the matter any further, which is — astutely chosen — about the only option that lets Gavin’s irritation dissipate under its own weight. Hank takes his cue from Connor and waits, steady, until Gavin deflates and leans back against the bedframe, knees held half-bent in front of himself.

“Who called in the body?” asks Gavin.

“Anonymous tip,” says Hank. “By the time the police rolled up, the whole compound had been cleared out. We figure a couple hours, at least, between the actual discovery of the body and the phone call.”

“They didn’t take the dogs,” says Connor. “The responding officers found them in the bedroom, door closed, still with the body.”

“That really fucking gets me,” says Hank. “Someone saw Landau dead, saw the dogs eating Landau, and chose to call 911 but not to let the dogs out of the room. What’s that about? Turns my stomach, to be honest.”

Sometimes, impatient for the minute hand to crawl to mealtime, Queenie and Rob would reach up to nip at his fingertips. A gentle toothless mouthing, coming away disappointed by the lack of scent on him. No hint of meat. At his soft chiding, they’d look up, eyes liquid like asking: What else was I supposed to do?

That, thinks Gavin. You were supposed to do exactly that. And if the thing within your reach was the broken face of your owner— still, what else were you supposed to do? He’d stopped bleeding, by then. They waited long enough.

“What did the toxicology report say?” asks Gavin.

“The dogs?” asks Hank. “Was it you that told us to go find them? Good thing you did, it would have been flushed out of them otherwise.”

“There were trace sedatives in their bloodwork,” says Connor. “Pentobarbital. It’s contextualizing information, certainly, but— I wanted you to clarify, why was it imperative that we establish this?”

“I thought it might narrow things down a little,” says Gavin. “The way they were with me, I know they’re a lot less aggressive with androids than with humans. Something to do with smell, maybe. An android could easily get close enough to take Landau out, without needing to go through the trouble of sedating the dogs.”

“But smell or not,” says Hank, “they wouldn’t just sit by and watch while their owner had his head progressively caved in.”

“Yeah, but why was his head caved in?” asks Gavin. “In your experience, why are victim’s heads usually caved in?” Victim, the word an ill fit in his mouth, like a loose tooth. Landau, a victim.

“When it’s personal,” says Hank. “Longstanding friction, turns into an argument, turns into a fit of rage, turns into something that looks like this. Except— that tends to be more spur-of-the-moment. You don’t walk in with a pocket full of barbiturates, intending to lose your temper.”

“Even granting that there was a measure of premeditation to it,” says Connor, “why sedate the dogs? Why not lock them out of the room, or just dispose of them altogether?”

“The sedatives weren’t meant to kill them, right?” asks Gavin.

“Some pains were taken to specifically avoid it,” says Connor. “It was a calculated dosage.”

Gavin tilts his head back until it rests on the edge of the mattress, the matelasse coverlet brushing against his cheek. Calculated. That’s what snags about it: the cold thread of deliberation running beneath the show of carnage, as though the gruesome spread of viscera were only so much misdirection. But misdirection from what? Why did the dogs need to wake up in a locked room to the stench of Landau’s blood?

His body, still warm. The Presas, whimpering for attention, nosing under his chin with their snouts, sweet and tacky with gore—

It’s less than he deserved, Gavin tells himself, forcefully enough that it carries a stamp of the truth. He turns towards Hank and Connor, who are engrossed in conferring about something over the far corner of the desk.

“For what it’s worth,” he calls over the low pitch of their murmur, “I do think it narrows things down. Who the fuck knows what this sedative shit is about, but an android wouldn’t put this kind of convoluted effort into just offing someone.” Jerking a thumb towards Connor: “He knows that’s right. I mean, unless Landau really pissed off an android somewhere along the way— but I doubt he even knew any androids well enough to piss one off.”

“Well,” says Hank, “apart from the one.”

“Thanks,” says Gavin. “Nines told you I wanted to consult? What’s next on your docket?”

“There’s the question of the murder weapon,” says Connor. “We’ll have some new leads once we hear back from the medical examiner.”

“You should call me when you do,” says Gavin.

“What’s in it for you, anyway?” asks Hank. “Sure doesn’t sound like you have high opinions about Landau — can’t blame you for that — so why run around trying to catch his killer?”

If I bury you, deeper than you can claw your way out, will that unshackle me from what you left behind? “I don’t know,” says Gavin. “Just want to see who got there before me, I guess.”

“I’m going to pretend I didn’t hear that,” says Hank.

“Put it in the case file, who cares,” says Gavin. “Better yet, put it in my file. You know the one.”

Hank drums his fingers on the desk, tracing the bright knife’s-edge of sunbeam that the window behind him casts on rosewood. When he speaks again, his voice catches in his chest a little, too thick to be smooth going.

“I was on leave, three years ago,” he says. “I’d like to say I would have done it better than they did, but I probably would have fucked it up, too. Still, they shouldn’t have— they should have looked after you.”

“It’s fine,” says Gavin. “There was that whole mess with PADLOC, I get it.”

He’s spent three years nursing his rancor, but Gavin can admit to himself that not all of it is built on solid ground. Even back then — when he stood in Jeffrey Fowler’s glass box of an office and all but begged him, let me work here — the pinched look on Fowler’s face was so harrowed that Gavin couldn’t hold the answer against him.

Right now, said Fowler, you’re an android confiscated from a criminal organization. But once this PADLOC bill passes—

That’s still months away, said Gavin.

I’m sure that excuse will go over well, said Fowler. We hired him before he became legally classified as a mob associate with pending felony charges, no harm done, everyone relax. Is that it?

Then what am I supposed to do now? demanded Gavin. You were the ones who took me away from—

Gavin, we didn’t take you away from anything! yelled Fowler, slamming a fist down on the desk. Gavin flinched at the rattle of the coffee mug, enough that Fowler stuffed his hand into his trouser pocket, abashed.

I know this isn’t easy to hear, he went on, but the best thing we can do for you is to have nothing to do with you. Get yourself cleared before PADLOC goes through, and you’ll be able to duck under the radar. But if we keep you here — sooner or later, some DA is going to come snooping around, looking for an anti-corruption case to make their career on — you want to be the first android thrown in federal prison? Or will you just fucking listen to me and lay low for a while?

So he slipped through the cracks in the system, for better or for worse. He was acquitted, PADLOC passed, and the DA’s Office left him alone. But hasn’t the bleeding stopped, by now? he thinks, as Connor levels his eyes to the balcony door handles, hunting for fingerprints. Haven’t I waited long enough?

“Did Nines give you my number?” asks Gavin, climbing to his feet.

“Yes,” says Connor. “Are you heading out?”

“I’ve had enough of this shithole,” says Gavin. “Really, tell me when you hear about the weapon. I promise I won’t get in your way.” Then, in the bedroom doorway, he decides that it can’t hurt: “Can you contact the shelter about something?”

“What do you need?” asks Connor.

“Nothing,” says Gavin. “The dogs, they’re called Queenie and Rob. I just thought they should know.”

Hank looks at him, and nods.

Outside, it takes a couple blinks for Gavin’s sensors to adjust to the afternoon light, the washed-out edges of the world resolving in fits and starts. Should have asked Nines for the sunglasses, he thinks, digging the heel of one hand into his temple.

The starched-collar devil in question is sitting on a lawn bench with his back to the colonnade, evidently messaging someone on his phone. The objection is perhaps too late in the raising, but it occurs to Gavin that this is strange enough to notice; even Gavin is capable of wireless communication without the aid of a handset, so it’s preposterous that Nines — bright as a new penny — should resort to a physical cell phone for his calling and texting needs.

At the sound of Gavin’s shoes on the paved portico, Nines turns around. “Are you finished here?” he asks, sunglasses gone, tucking his phone away.

A simple yes is all Nines needs from him, but Gavin stills with the word lodged in his throat, waylaid by an unfamiliar sensation. Someone, waiting for him. Someone — not someone, but Nines — made for better things than this, worth a thousand of me — waiting for him, dappled in the pattern of the leaves overhead. Inside his chest, the thudding of his heart echoes like the monsoon rain.

“You’re still here?” asks Gavin, absurdly.

“Don’t look a gift Chevy in the mouth,” says Nines, and unlocks the doors with the keyless fob. The car chirps to life, ignition, a rolling hum.

Try as he might, Gavin can’t find the radio station with the car lot commercials. He settles instead for a grab bag of highway rock, the thunder of guitars big enough to fill the sky, the fearless sweep of the open road.

Chapter Text

5.

River Rouge tries to ward them off with weather. Less than half an hour from downtown, and the water dies along the way, unglinting; the grey only gets greyer as they head southwest, overcast to a flatness that robs the shadows from the street. When Nines pulls into a parking lot off the stretch of West Jefferson, the cadaver of the steel mill graces the rear window with its spectral silhouette. Beyond it, a lopsided smudge, the ruin of the unfinished Gordie Howe Bridge.

“Kamski giveth and he taketh away,” says Gavin.

“U.S. Steel was already on its way out,” says Nines.

“Sure,” says Gavin, “but how am I supposed to throw darts at a picture of a trade war? Even if retaliatory tariffs had a face, it still wouldn’t be as punchable as Kamski’s.”

Nines sweeps a careful eye over the empty parking lot, the nighttime neon drained from the Frankie’s signage above the door. Customary dead hours for a dockworkers’ bar, a hair before noon, between the last call and the liquid lunch. Theirs is the only car in sight.

“Our boy’s in there?” asks Gavin. “Pete?”

“Should be,” says Nines.

Pete Nemeth, proud union rep for Local 422, drops by Frankie’s every Monday just before opening. The eponymous Frankie is more than happy to pour an early pint for his regular, but — as it turns out — happier still to supplement his income with a courtesy fee from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, in exchange for making himself scarce in the back for half an hour or so. That’s half an hour for Nines to accost Pete, to scrape together what a union man knows about the latest red ice waterways out of Detroit.

Gavin swings the passenger door open. He gets one foot on the ground, before Nines turns and sees him.

“Gavin,” says Nines, “stop.”

“Relax, Jesus,” says Gavin. “You’ve made it very clear that I should wait outside the bar.”

“So where are you headed?” asks Nines.

“Let me get some fresh air,” says Gavin, “before I go for a joyride in your precious Malibu and do donuts on the graveyard of the domestic steel industry.”

Nines doesn’t let him get away with it. “Really,” he says, “headed where?”

“Come on, I can’t sit in this car the whole fucking time,” Gavin tells him, and shuts the door in his face. Then, when Nines follows him out of the driver’s seat: “Can I stand outside, by the front door? At least?”

“By the front door?” repeats Nines.

“Yeah,” says Gavin. “You know, like security detail.”

“You’re not—” begins Nines, then purses his lips closed, shaking his head. Gavin takes it as permission denied and is mustering up a last objection, except that Nines says, “Outside the door is fine,” and locks the car behind him.

So what was he shaking his head about? There’s a whiff of stale ash as Nines steps inside Frankie’s, a whorl that dissipates in his wake, the entrance creaking closed. Gavin takes a seat on the doorstep, scraping his soles against the pavement. Part of him had hoped that he’d overhear a snatch of something, hanging around like this, but the door’s too heavy for him to pick up anything from the inside. Just the flurried beating of a seagull’s wings next to him as it descends on a wayward french fry.

Well, Nines will apprise him of the conversation later. Despite what Nines may think, Gavin isn’t unreasonable; he understands why this is as far as he can tag along, that his go-ahead to ride shotgun on the case doesn’t mean he gets to work it like an agent. If Pete’s likely to spook, better for Gavin to stay out of the way and let Nines handle it. Sure.

“I’m just consulting,” Gavin tells the seagull. “All this is above my pay grade.”

It’s been more than half a century since organized crime had its claws in the unions like they used to, but that doesn’t mean a little extra lining for the pockets doesn’t go a long way, still. Gavin never spared much thought for the brass tacks of Landau’s empire — it was just a postscript appended to the thing he cared about, like boilerplate copy or state income tax — but he learned bits and pieces along the way. The long chain of who gets paid off on the docks to sneak a shipment of ice onboard, the contractors, the USDA officials, the circuit court judges, the union reps.

Maybe Pete’s on the take, maybe he isn’t, but they’re not here to shake him down for petty cash favors; besides, it’s not protocol anymore to antagonize unions, said Nines. Whatever his level of involvement is, Pete’s position means he’s kept abreast of any recent disturbances in the port ecosystem. They’re here for what he knows.

“Or that’s what Nines is here for,” says Gavin. “I’m mostly here to get out of the house.”

A second seagull alights next to the first, challenging its sovereignty over the french fry. The french fry in question is big enough to satisfy both birds, but a squawking scuffle ensues anyway, which is a metaphor for something or other. Even with absolutely nothing else to do, Gavin isn’t given to exegetics.

It’s not so bad, this absolutely nothing else to do. He’s used to being the contingency plan, the let’s hope it doesn’t come to that, only standing close enough to step in when he’s needed. Here, he isn’t even that — why would he be, when Nines is more than capable of looking after himself — but it’s become a kind of familiarity nonetheless, the rhythm of their routine. Nines pulling up at his place. Gavin slipping into the passenger seat like a sword into its sheath, the angle of the chair just the way he left it.

Nines waits, and drives him home. Nines waits for him. The warble of the car alarm when he sees that Gavin is ready to leave, a songbird greeting: I’m still here. Something about idling outside a decrepit bar while Nines does his job feels like paying back a debt, even if it doesn’t do a thing to help the case. I’ll be here when he’s ready to leave, thinks Gavin. That, at least, I can do just as well as he does.

“I don’t like owing people things,” Gavin says to the otherwise preoccupied seagulls. “And it sure beats sitting around at home, you know. It gets really—”

Something shifts.

Gavin’s on his feet before he knows it, danger, all his sensors cranked up to high alert, the clacking of the seagull beaks like dry thunderclaps. For a hot, dizzying moment, he can’t pin a reason to his panic, every inch of his skin prickling with a tension unasked for; it’s so sudden that he wonders — is it a glitch? — the road as empty and still as when they came, no hint of trouble from inside the bar. Am I losing it? He presses his palm to the door, out of breath.

Nines. No, why would it be Nines? Gavin would have heard him reach out over the comm line, there’s no way anything in this run-down hovel could incapacitate Nines quickly enough to shut him down before— or shut him down at all, for that matter, Gavin thinks, measuredly, but he doesn’t trust the measured part of his brain half so much as his gut — he wasn’t made to reason things out, he was made to react quicker than he can explain himself — so by the time he gets to surely it can’t be Nines, he’s already throwing the door open and charging in.

It’s so dark inside that it blinds him. Like waking up at CyberLife, his eyes wide, nothing to see. Not even the telltale glow of Nines’s LED, ditched in the cupholder in the car — ah, shit, Gavin remembers, I’ve still got mine on — but quicker than his sight returns to him, he hears Nines, piercing through his head like a bolt of light.

What comes through isn’t English; it’s not exactly language of any kind, not even machine code, lacking the precision that touch-based interfacing would allow. More a jumble of affect than anything else, a projection of an attitude, broad and gestural. Untangled, it turns out to be something like:

why are you here

The question is so unmistakably Nines-as-usual that it saps all the dread clean from Gavin. He’s okay. Far from polite, but in the relief that floods in to fill the empty spaces, even the brusqueness feels like— warmth, after a fashion. Clutching to it like a strand of yarn in a maze, Gavin lets Nines’s terse demand guide him back into the bar.

“—What the fuck,” says the man at the bar that isn’t Nines. Pete Nemeth. As soon as Gavin sees him, one thing becomes patently obvious; this bastard’s going to bolt, thinks Gavin. It doesn’t take his knack for snap judgment to figure as much, Pete’s stool already angled away from Nines, his heel braced against the foot ring, shoulders drawn up to his ears.

Nines’s second attempt at communication comes through instantly: he doesn’t know who i am

And if that isn’t interesting. Nines, half-heartedly covert. “Is this going to be much longer?” asks Gavin, making a show of louche impatience. “I gotta be back in the city by noon.”

“Unfortunately,” says Nines, “Mr. Nemeth has been less than forthcoming.”

“That’s what I get for sending in a bookkeep to do grown-up work,” says Gavin. Behind Pete, Nines raises an eyebrow at bookkeep, so Gavin appends an explanatory note: you have cpa face

Things are starting to fit together. Nines is, apparently, undercover; that is, if desperately trying to come off as anything but an FBI agent even qualifies as a cover identity. Pete must have started off on a skittish foot. The sideways tilt of dread that brought Gavin to his feet — not Nines in danger, per se, but — it was linked somehow to Nines’s own spike of panic, watching Pete inch closer to the breaking point of his suspicion.

“Bookkeep for who, for you?” Pete asks Gavin, looking him up and down.

“Oh, not me,” says Gavin. He leans against the bar on Pete’s other side, hemming him in. “Pete, listen, I don’t know if our accountant made it clear, but this isn’t about you. We don’t care whose grease gets on your palms on your own time. Couldn’t give less of a shit about you. Does that hurt your feelings?”

“Fuck off,” says Pete. There’s sweat beaded on his hairline.

“We know how it is here, okay?” says Gavin. “So we don’t like it any more than you do, when someone you’ve never even seen starts nosing around the docks, throwing money around, trying to weasel their way into shit that’s no business of theirs. It disturbs a— certain fine balance, I think you’ll agree. One that people like you and me have put some very fucking hard work into.”

Despite all odds, Pete’s pulse begins to slow. Jumpy with cops, then, but immediately at ease with anyone who appears to have their hands in questionable economies. Gavin might not know all the ins and outs of Nines’s case, but he knows the cadence of this side of the tracks, the physical vernacular of misconduct. Pete recognizes Gavin as a type that fits a mold, the echo of a hundred others just like him that pass through Frankie’s, all of them up to no good. A bagman collecting his dues at the close of every week. A driver rolling his tinted windows down as he drops off a shipping pallet of crates. Scuffed, in a way that Nines can’t inhabit.

“But guys like him and me, we don’t work the docks like you do,” Gavin tells Pete. “That’s why we’re asking for your help, Pete. We just need to know who the asshole is that’s been shitting all over your well-kept house, and we’ll go have a word with them. All right? Let them know that’s not how we do things around here. Isn’t that a load off your hairy back?”

Pete stares at the LED steady blue at Gavin’s temple; then a quick dart of his eyes back towards Nines, who is idly drumming his fingertips against the condensation on the pint glass.

“You’re not a cop?” Pete asks Gavin. “He’s not a cop?”

“You think I look like a police android?” asks Gavin. “Fuck, Pete, don’t be stupid. Him, I get — just look at him — but if he ever was a cop, let me tell you, he definitely isn’t one anymore after the kind of shit he’s done for us.”

This is, as far as lies go, a plausible one. Nines may not look the part of a garden-variety hoodlum, but he makes a fairly convincing CPA with a vicious streak. When Pete glances back at him again, Nines shrugs with one shoulder, his gaze chillingly flat.

“I don’t want to make trouble,” mumbles Pete.

“Of course not,” says Gavin, soothing. Jesus, I guess some opportunistic piece of shit really has been poking around the docks. Landau must be spinning in his county morgue locker. “We’re just going to talk to them, that’s it,” he continues. “Sometimes people fuck up because they don’t know any better, that’s not their fault, but how are they going to learn if no one tells them that they’re fucking up?”

Pete blows out a lungful of breath, poised like a marble on the lip of a table. His hesitation is tantalizing, sweet as blood; Gavin feels the simmer of something a little like prey drive in his veins, the singing urge to chase this down until he has it between his teeth.

This, he thinks, I know. I can do this for you.

“Shit,” says Pete. “Who are you? Did you say?”

“Where are my manners,” says Gavin. “That sack of meat to your left, his mother calls him Richard— so we call him Rico.” Nines levels a single forceful no at him, which he ignores with great pleasure. “My name is Gavin. Take down my serial if you like, you can go look my file up at Central Station. I’ve been in and out,” a dusting of credibility that has the benefit of being the truth.

Pete shakes his head to decline Gavin’s serial number, satisfied with the offer. “And you do—” he prompts.

“We transport,” says Gavin. “I oversee some— delicate business that would prefer not to deal with disruptions to the status quo.”

“Delicate business, huh?” asks Pete.

Gavin doesn’t know what it could be — what’s become trendy to smuggle over the last three years, I’ve really lost touch with my disreputable roots — but before he can stumble, Nines shows him an image. Evidence photograph. A shipping container pried open, vacuum-sealed bags of disassembled android parts, each hermetic packet bulging with a head, a torso, two arms, two legs.

“Here’s the thing about androids,” says Gavin, holding back the bile. “We’re built to be resilient. Things that would irreversibly damage humans — a long sea journey in a cargo hold, for example — no problem for an android. Take them apart before the outbound, put them back together at the destination, and they’re — well, let’s say they’re — good to go, if you catch my drift.”

Pete, to his nominal credit, also looks like he finds the whole idea rather unpalatable. “That stuff, yeah,” he mutters. “I get it, fucking Christ. Don’t you— aren’t you an android?”

“What gave it away,” says Gavin.

“I don’t— how can you do that to your own—” Pete trails off, unaccustomed to the moral high ground.

“How any of us does any of it,” says Gavin. “Got a taste for the easy life, I guess.”

Pete heaves a huge sigh, so unhappy that Gavin feels bad for him. Nines was right to pull android sex trafficking out of the hat. Unsavory enough to discourage any questions from Pete, a looming suggestion that they — or whoever they work for — would have no qualms about getting what they wanted out of him.

“We need to leave soon,” Nines says to Gavin, “if you want to make your twelve o’clock.”

“Well, Pete?” asks Gavin. “Am I going to make my twelve o’clock?”

“—Fuck,” says Pete, the word drawn out into multiple harrowing syllables. He gnaws on the inside of his cheek, picks at the seam of the beermat with his thumbnail. At last, he takes a deep breath and says: “Look, I don’t want— you gotta promise you won’t make this a whole thing.”

The rush of excitement is so immense that it hits Gavin like a physical force, a blow to the pit of his stomach. I did it. God, the pounding, screaming, delicious wide-eyed firework thrill of the hunt. He’s buzzing with the victory high, ringing in his ears. I did something that only I could do. Thrashing between his teeth, a kill.

“We won’t,” he says, fist clenched tight in the pocket of his jacket, just to keep his tone level.

“Come down on Thursday night,” says Pete. “I can introduce you to some of my guys, they’re the ones I’ve been hearing about this from.”

“I’ll be there,” says Gavin.

Behind Pete’s back, Nines’s hand comes shooting into Gavin’s pocket. Gavin only has a fraction of a second to register the contact — the brush of Nines’s fingers against his palm as the grip closes — cool to the touch, like I imagined he would be — then Nines overrides his security protocols like they’re fences built from toothpicks, peels back his liquid skin, an unceremonious husking.

Gavin is so startled that he lets it happen without a fight, suddenly wrenched open to the connection. —Nines? he ventures, uncertain.

Please listen, says Nines. His voice is almost too stark to bear, unhindered by the two-bit wireless link between them or the machine constraints of their parts. Speared like a fish, it takes Gavin a moment to parse the words he hears next — Gavin, you can’t go — but when he does, the betrayal stings that much sharper for how fast he’s flying. Can’t go? After all this?

“Why not?” he demands out loud, forgetting himself.

“What?” Pete asks in confusion.